Share

How we’re integrating heritage conservation and transit planning

Protecting Victorian-era industrial architecture at 500 Howard St. in Oshawa.

Jul 24, 2025

For Thomas Wicks, heritage preservation isn’t just a job — it’s a calling.

As the Environmental Programs and Assessment manager in charge of cultural heritage at Metrolinx, his work blends the past and the future in unexpected, transformative ways.

Thomas Wicks, Manager Environmental Programs and Assessment - Cultural Heritage at Metrolinx. (Metrolinx Photo)

“My personal passion is my profession,” he says. With nearly two decades of experience conserving historic sites across Ontario — including roles in high-profile projects such as the Don Jail and the Evergreen Brick Works — Wicks holds a deep belief that heritage buildings aren’t meant to be frozen in time, but adapted to new life.

“There’s a common misconception that heritage means keeping things as they were,” he says. “But really, it’s about managing change, not resisting it. It’s about finding new uses and new meaning in places that have value.”

That philosophy is at the heart of his work at 500 Howard St. in Oshawa, a site with more than a century of industrial and community history that was preserved as part of future transit expansion.

New uses for old structures

“Old buildings can adapt to new uses” he says , echoing a belief that has guided his contributions to projects like the Evergreen Brick Works — once a crumbling industrial site in Toronto, now a vibrant community and environmental hub.

That same approach is now being applied to 500 Howard St., which might look like an aging industrial complex at first glance, but carries enormous historical weight in the story of Oshawa’s development.

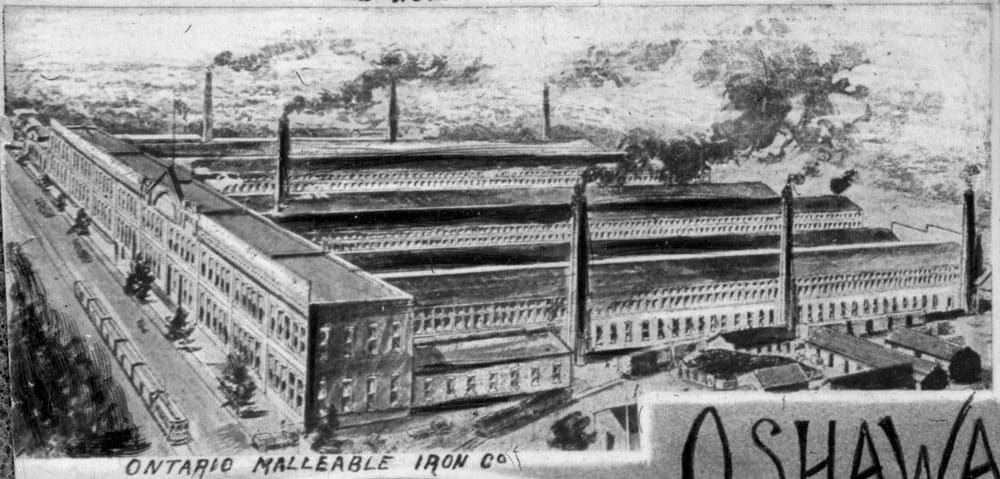

Originally built in the late 19th century, it was home to the Ontario Malleable Iron Company (OMIC), a foundry that played a major role in the province’s industrial growth. For decades, the plant produced malleable iron, an adaptable material used across manufacturing sectors.

The Ontario Malleable Iron Company

“The ability to create malleable iron really impacted the industry in Ontario and in Canada as a whole,” says Mattia Thillaye-Kerr, a heritage consultant with ERA Architects. “At one point, malleable iron had to be imported from Great Britain and the U.S., so manufacturing it locally was a game changer.”

Strategically located near major rail lines, the foundry became a hub of employment and economic activity.

“They at times had employees numbering in the hundreds,” says Lisa Terech, community engagement coordinator at the Oshawa Museum. “I think at one point they topped out at over 800 employees…at one point they were employing more people than Oshawa’s General Motors plant, which I think is quite remarkable.”

After the OMIC shut down in 1977 following a workers’ strike, the building sat dormant until 1980, when Knob Hill Farms purchased it. In 1981, it was converted into one of the grocery chain’s large-scale “food terminals;” its rail access and proximity to Highway 401 made it a convenient hub for transporting goods to stores.

Knob Hill Farms closed in 2000, and the site remained largely vacant — a quiet presence on the city’s industrial landscape waiting for its next chapter.

Steve Stavro at Knob Hill Farms at Dixie Plaza (now Dixie Mall). The Globe and Mail, October 16, 1978. (Source: jbwarehouse.blogspot.ca)

Integrating heritage preservation into transit planning

“When I joined Metrolinx, this was the first file I was given,” Wicks says. “To be honest, I was unfamiliar with 500 Howard before, but as I started learning about it, I saw how much it aligned with what I care about — how to balance infrastructure growth with meaningful conservation.”

Metrolinx purchased the property in 2014 as part of broader GO Expansion planning, including future rail service to Bowmanville. Early assessments flagged the building as having significant cultural heritage value, and we began a thorough evaluation of the site, determining what should be preserved and why.

One portion stood out: the original 19th-century brick structure, now referred to as “Part 1.” Though weathered, it was a rare surviving example of Victorian-era industrial architecture in the region.

Aerial view showing Part 1 (heritage building) highlighted in yellow and Part 2 (warehouse) highlighted in red. (Source: Bing Maps, annotated by ERA)

“Oshawa’s growth included so many industries that by the end of the 20th century it became known as the Manchester of Canada,” says Catherine Riddell, heritage consultant with ERA Architects. “The city had textile manufacturing, tanneries, sawmills, and more — all connected by a rich transportation network.”

Preserving the past, for the future

“Sometimes people think heritage work is about polishing things up to look the way they did a hundred years ago,” Wicks says. “But that’s not always the goal. We had Part 1 stabilized, making sure it’s secure and watertight, and safeguarded so that it can be reused at some point in the future.”

That process, known as mothballing, involved reinforcing the structure, securing access, and preventing weather or fire damage while long-term plans are being developed.

“If you don’t make the investment now, you won’t have the resource five or 10 years from now,” he says.

Investing in smarter, more sustainable infrastructure

For Wicks, preserving 500 Howard isn’t about nostalgia. It’s also about sustainability and protecting a sense of place in the community.

“These places have embodied energy — the energy that went into making the bricks, cutting the timber, constructing the structure,” he says. “Preserving it adds value to the community and gives it a sense of place.”

By integrating heritage preservation into transit planning when feasible, we are protecting Ontario’s architectural legacy and investing in smarter, more sustainable infrastructure.

The future use of 500 Howard St. is still taking shape. But now it’s protected and positioned to serve the community once again.

“Whether people live here, work here, or just pass through on their daily commute, they’ll see this building and they’ll know that it matters,” Wicks says. “It’s not just about what it was. It’s about what it can be.”

by Nadiia Fokina Senior Advisor, Capital Communications, Travis Persaud Metrolinx capital communications manager