Share

A not-so-boring history of tunnel boring machines

The evolution of tunnelling machines and the Canadian breakthroughs that changed the industry.

Sep 10, 2025

From Rexy and Renny to our literal rock star Diggy Scardust and now our latest pair Libby and Corkie, tunnel boring machines (TBMs) are a marvel of engineering vital to building transit. But did you know these cutting-edge machines can trace their origins back over 200 years and that they were directly inspired by nature? Or that tunnelling innovations in Canada changed the industry forever?

Let’s dig into it a bit.

The tunnelling shield

In the early 1800s, Anglo-French engineer Marc Isambard Brunel wanted to do what seemed impossible at the time: build an underwater tunnel. Though there are legends of a Babylonian tunnel under the Euphrates river, no physical evidence exists, leaving no precedent for him to build on. But where humanity struggled, nature held the answer.

Brunel once worked at a shipyard and in a letter, recalled the handiwork of a critter that bore through the ship’s submerged wooden hulls while secreting a substance that hardened its new burrow. Its behaviour directly inspired his “tunnelling shield.” Patented in 1818, it is the first chapter in the story of the TBM.

A scale model of the tunnelling shield at the Brunel Museum in London. (Photo courtesy of Dunks58)

His creation allowed workers to safely excavate as masons lay protective brick tunnel lining. South African engineer James Greathead would expand on this idea further.

The Greathead shield in use during the construction of a railway tunnel. (Courtesy of The Engineer, July 26, 1895. James C. Cole)

Greathead developed ideas still used in tunneling today, like the use of sprayed concrete (shotcrete) and pre-cast tunnel lining. His work was vital to completing London’s first Tube tunnel, earning him the nickname, the father of The Tube.

Remnant of a Greathead shield (painted red) left underground during tunnelling in the 1890s, rediscovered nearly a century later. (Photo courtesy of Matt Brown)

Mechanizing the method

Though tunnelling techniques were advancing, excavation was still a laborious and dangerous task, especially when using early power tools and explosives. The first attempts at machine excavation rarely worked outside of trial tests. But in the late 1800s, British army officer Frederick Beaumont succeeded.

The Beaumont machine was the first real TBM success story, able to work reliably and continuously for over 50 days. (Wood engraving by Auguste Tilly, 1883)

His machines would collectively tunnel 3,700 metres in an attempt at a tunnel between England and France. They were reliable and fast, too, digging 15-25 metres per day.

An early example of mechanized tunnel extraction. (British Pathe, 1909/1910)

Making history at the Humber River

TBM innovation would largely grind to a halt for nearly a century at this point. The complex, expensive machines didn’t see much use outside of the mining industry. But fittingly, it was mining engineer James Robbins who defined what a modern TBM is when he was tasked with digging the tunnels at South Dakota’s Oahe Dam.

His machine, called the Mole, used spikes and cutting discs on a rotating face for tunnelling. And to his delight, it was extremely successful.

The cutting face of Robbins’ ‘Mole’ machine. (Courtesy of miSci, Museum of Innovation & Science)

The first real modern TBM was here. And Robbins would refine the machine further on Canadian soil.

James Robbins at the site of the Humber River sewer tunnel. (Robbins TBM photo)

In 1956, the Mole was tasked with digging the Humber River sewer tunnel in Toronto. Harder rock at the dig site wore down and broke the spikes on its cutting face, frequently pausing work so they could be replaced. Costs and frustrations built to the point where Robbins removed the spikes altogether. And as it turns out, the cutting discs had been doing the real work from the start.

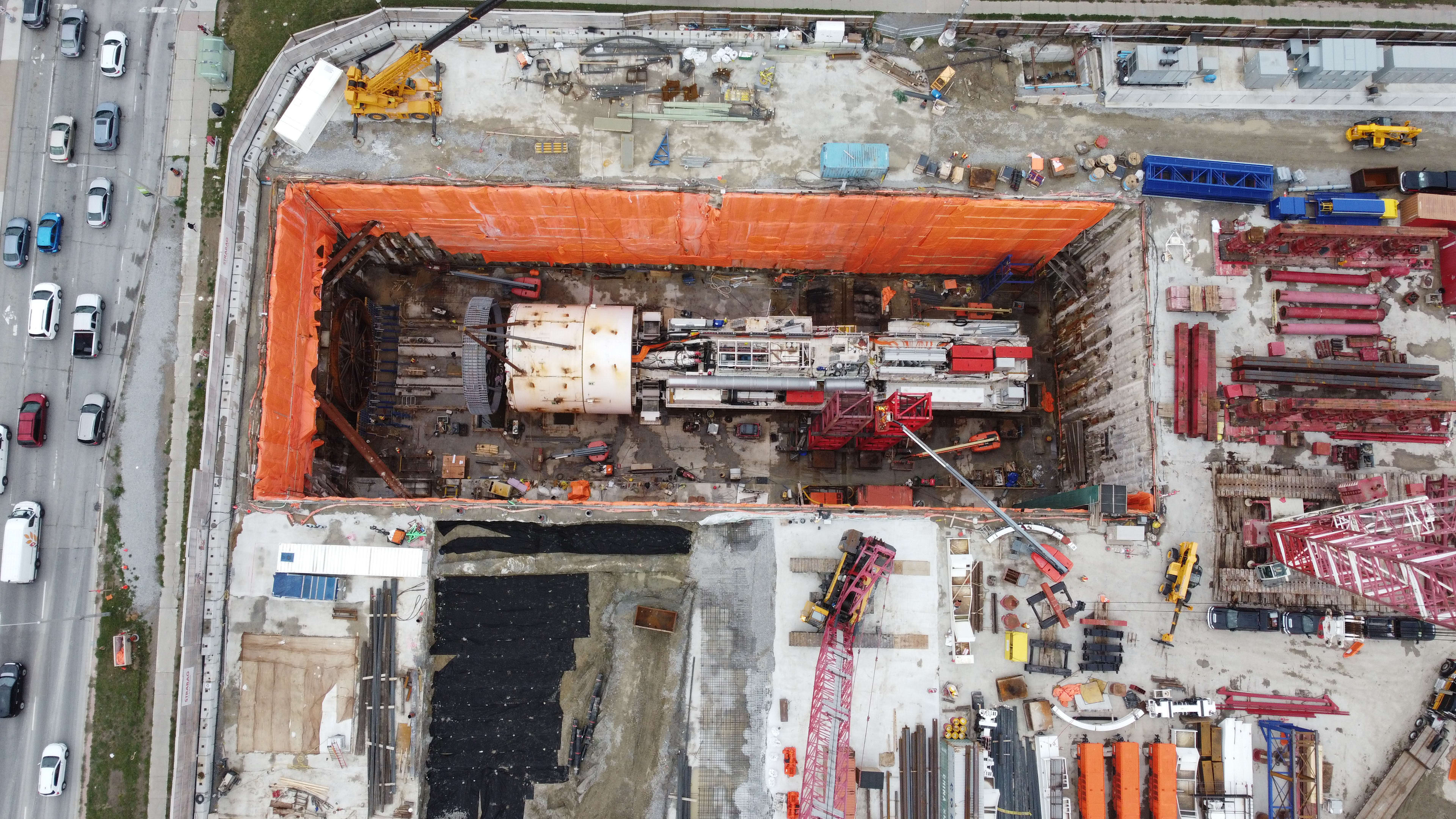

The cutting head of a TBM for the Eglinton Crosstown West Extension. Note the cutting discs painted blue. (Metrolinx photo)

Robbins also incorporated a system of scoops and a conveyer belt to help automate and speed up excavation.

A Canadian tunnelling breakthrough

By this point, TBMs had largely perfected the dig. But lining an excavated tunnel still required heavy lifting. Modern TBMs can lay precast segments as they dig. But how did we reach this point? You can thank a Canadian.

Rexy and Renny have collectively installed over 52,000 pre-cast concrete wall segments.

In 1978, Italian-Canadian Richard Lovat patented the one-armed bandit: a device to mechanize the tunnel-lining process. One year prior, he used it when digging the Neebing-McIntyre sewer tunnel in Thunder Bay. It's a Canadian innovation that set a new standard for TBMs going forward.

Patent image showing Lovat’s device for adapting a TBM to handle precast tunnel liner.

Present and future of TBMs

TBMs play a vital role in tunnelling and excavation around the world. Exciting developments like zero-emission TBMs are in development. There are even TBMs that use plasma cutters instead of cutting discs. For every type of ground, from hard rock to wet soil under water, there is a TBM made specifically for it.

At Metrolinx, we use these behemoths on the Eglinton Crosstown LRT, the Eglinton Crosstown West Extension, the Scarborough Subway Extension, the Yonge North Subway and the Ontario Line subway.

They are one of the most powerful tools in connecting communities as we work to build and expand transit across the region.

by Shane Kalicharan Metrolinx Editorial Content Producer